When I first placed objects between piano strings, it was with the desire to possess sounds (to be able to repeat them). But, as the music left my home and went from piano to piano and from pianist to pianist, it became clear that not only are two pianists essentially different from one another, but two pianos are not the same either. Instead of the possibility of repetition, we are faced in life with the unique qualities and characteristics of each occasion. The prepared piano […] led me to the enjoyment of things as they come, as they happen, rather than as they are possessed or kept or forced to be.1

In the late 1930s, days before she was due to perform Bacchanale, dancer Syvilla Fort (1917-75) asked experimental composer John Cage (1912-92) to write some accompanying music. Cage agreed, and would have liked to compose for percussion, but the venue had neither pit nor space in the wings for musicians. There was just enough room for a piano, situated to one side of the stage, so he decided to write for that. Cage experimented by placing various household objects inside the instrument — a kitchen plate; metal nails — wanting to adapt the sound of the piano to make its tone more percussive. He discovered that inserting screws and bolts between the strings made the type of sound he wanted while also staying in place while the piano was played. Thus, ‘the prepared piano’ was born. Cage and his new instrument worked together to create the piece for Bacchanale; and Cage went on to compose many works for prepared piano throughout the 1940s and 50s.

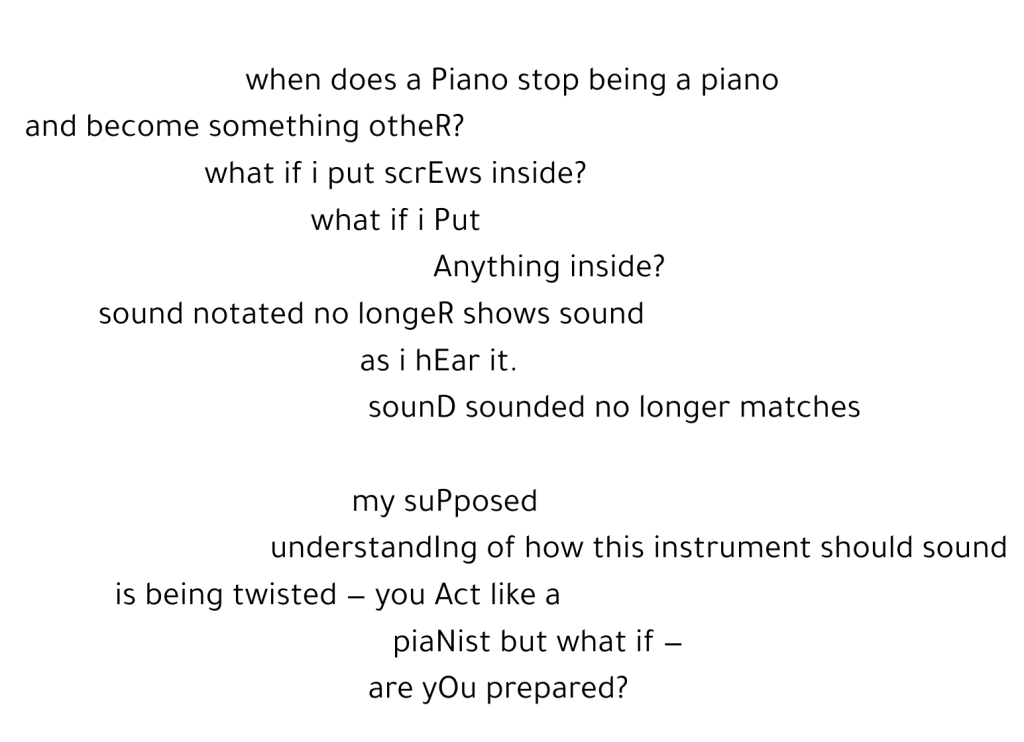

Where a prepared piano is used, its behaviour challenges the traditional roles of everyone involved in the musical process. The composer is writing for an instrument whose sound is unpredictable and vastly varied. Each prepared piano is unique — even more so than standardised instruments — because part of its manufacture is determined by the performer. As a result, the same musical notation will produce an incredibly wide array of results. The notation no longer depicts sound anticipated, but rather action anticipated. The performer, who carries out the preparations prior to, or during, performance, is forced to take on numerous additional creative decisions, and must learn to detach their actions from the resultant sound they have come to naturally expect. But the challenge is perhaps greatest for the audience member, who watches a pianist playing a piano, but hears a quasi-percussion ensemble. Cage broke with tradition by physically breaking what the piano was understood to be: he disrupted its sounding mechanisms, rendering it impossible to make the piano sound as it classically should. As such, the instrument sparks numerous questions regarding what comprises a piano, and what constitutes a musical instrument. When does a piano stop being a piano and become something new? A prepared piano is no longer a piano if a piano is the sound it makes, because its sound is drastically different. But the prepared piano might be a piano if a piano constitutes a specific physical structure, technical build, or appearance.

Piano preparations are reversible and non-standard, which renders the life of any particular prepared piano relatively short. However, the prepared piano has a long-lasting legacy. Its techniques are now commonly heard across genres including jazz, contemporary classical, popular, and film music. As such, the musical instrument has been freed from its physical object. Fluid and changeable, the prepared piano as a musical instrument can be understood to encompass all prepared pianos since the Bacchanale: each time preparations are set in place, the instrument is taken out of the case; and whenever they are removed, the instrument temporarily returns to storage.

footnotes / list of references

- Cage, John, “How the piano came to be prepared,” John Cage: Official Website, 2012, https://www.johncage.org/prepared_piano_essay.html. ↩︎

Leave a Reply