‘Creative by constraint’ is a seemingly contradictory statement, often disputed by scholars who believe that full artistic ‘freedom’ is only found in free improvisation (for example, see: Barrett 72; McKay 69). However, notation can free an interpreter from their own subconscious constraints by narrowing their interpretational path:1 a notated score guides a musical practice towards an otherwise unconsidered approach. In this sense, imaginative freedom comes by the exploration of a musical space to which an instrumentalist’s own practice may not have led.

literature on this topic

Bayley & Heyde state that: ‘the limits of notation can provide creative tension and imaginative interpretation’ (80). Composers such as Cornelius Cardew and Michael Finnissy acknowledge notation’s creative affordance:2 Cardew describes the ‘creative activity’ of notating music (21), and Finnissy uses notation to ‘“enabl[e]” the performer’s active engagement’ through its limitations (Bayley & Heyde 81). Bayley & Heyde argue that, by the notational complexity that sparks communication between the instrumentalists interpreting the score, Finnissy’s scores become ‘something in [themselves]’; ‘a second interlocutor [to the composer]’ (82). In line with Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory,3 this description highlights notation’s role as a creative agent, collaborating with human and non-human agents in the distributed process of music-making.

the need for notational constraint

Interpreters inevitably call on prior knowledge when approaching a musical score,4 because the realisation of any notation — and especially contemporary notation (Eco) — requires creative decisions of an interpreter.5 When a notated score does not balance freedom with constraint, all realisations hold a ‘predictable aesthetic’ (Anderson & Dingle 138), stifling the interpreter’s creative potential. In this respect, complete notational sparsity often fails to successfully encourage creative freedom (Anderson & Dingle 138 and 325),6 because the score does not sufficiently guide the interpreter’s approach.7 Instead, decision-making relies heavily on the interpreter’s own preferences and so, rather than encouraging a more novel (‘free’) approach, interpretations of such scores become homogenised. I argue that notation is only ‘consistently useful’ (Benjamin)8 when it acknowledges the equal roles that composer and interpreter have in the distributed musical process, depicting constraint and freedom accordingly.

lars bröndum short circuit (2004)

Composer Lars Bröndum describes how performances of his piece Short Circuit (2004) are surprisingly consistent, despite the score’s sparse notation. Bröndum attributes this to the instrumentalists being relaxed and therefore ‘able to tap into their improvisational skill at a deeper level’ (643); but it seems more likely that the recording by ReSurge ensemble (for whom the piece was written, and of which the composer himself is a member) has heavily influenced subsequent interpretations.9

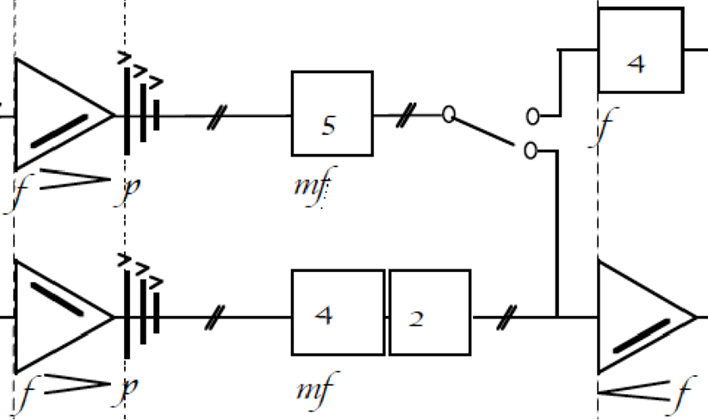

For example, see Fig. 1. When performing the box labelled ‘5’, the instrumentalist is to improvise with any group of five notes. Despite this supposed freedom, Bröndum remarks: ‘[t]he piece sounds surprisingly similar in the different ensemble settings’. Surely this is because musicians faced with a choice of notes will almost inevitably fall back on their own sonic preferences, unless the score constrains these in some way? Any musician playing box ‘5’ will be listening and adjusting to their musical surroundings, consciously or unconsciously, especially because they are working in harmony with other instrumentalists. If the musician has a background in tonal music, for example, there is a high chance that they will favour consonance over dissonance. Therefore, the result is not creative ‘freedom’; it is, in fact, heavy reliance on the interpreter’s prior musical preferences. Notation stops being consistently useful when it does not offer enough clarity by constraint; it stops being a good tool of, or conduit for, communication between composer and interpreter. This is emphasised by Benjamin, who said:

[i]f it’s a good relationship [between me and the composer] and the score is carefully critiqued, and [the composer has] got a rigorous process and there’s an authenticity in the sense of them living with that practice and growing with it. Then I really do think both [composer and instrumentalist] voices get heard. And where the voices don’t both get heard… Well, my voice is always heard, because it’s my fiddle you’re hearing, you know?

Where the notation leaves too much to interpretation, the instrumentalist — whom the composer intends to ‘free’ — is in fact more bound than ever by their own constraints. As Benjamin states, it is only the instrumentalists’ voice (and preferences) that are heard in this situation.

amy bryce storyteller (2021)

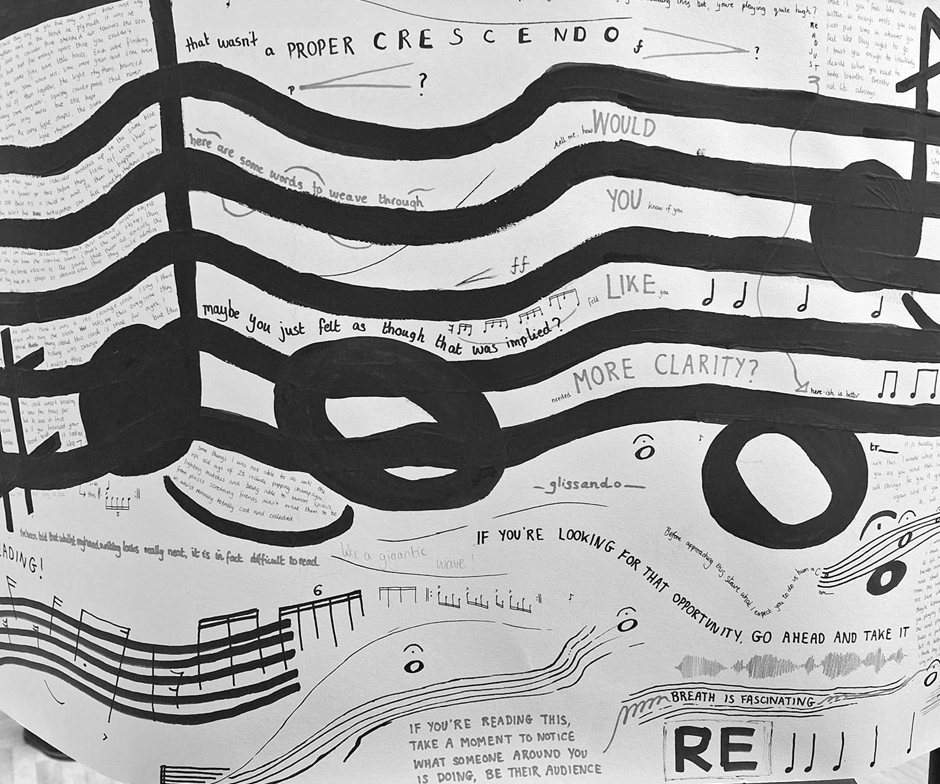

Bryce’s handwritten scores highlight a unique notational approach where carefully considered constraint allows interpretational freedom, eliminating total ‘ambiguous subjectivity’ by complexity. Take, for example, the five-metre score for Storyteller (2021) (see Fig. 2).10 This notation prompts improvisation with certain constraints, so that interpreters have the freedom to engage with the music, musicians and surroundings, while being led with clear focus. The score’s openness and non-linearity leads to a musical outcome that is recognisably different every time.

The score is incredibly complex, with numerous types of notation in varying sizes offering many ways for an interpreter to engage with the material. Standing far away, an instrumentalist could respond to the shapes implied by condensed text; or to the very large stave that stretches across all five metres. Closer, one might read the written text, perhaps speaking it aloud or using an instrument to realise interpretation in pitch. Staff notation is available for any instrumentalist who prefers depiction of approximate pitch; otherwise, one might interpret the shapes of staff notation, or read the text, or respond to Bryce’s hand-drawn illustrations. A vocalist (for example) would be able to move around the space to find new perspectives; whereas an instrument that is physically static, such as a piano, limits the amount of the score that can be seen. (The pianist’s view will also become interrupted by any musicians walking in between the piano and score.) Such constraints are not explicitly written in the notation, but are brought about by the notated score; by its nature as a large physical object, and by its presentation. Thus, the interpreter is continuously required to make creative decisions, all of which are guided (or afforded) by the notated score.

The score for Storyteller also requires discussion amongst interpreters; conversations regarding boundaries that might be set before or during a performance. For example: ‘let’s play quiet things quickly, and loud things slowly’; or, ‘this time I will only respond to shapes I see’. Thus, the notated score is found to generate conversation and movement. Whether traditionally rehearsed, practised, and performed or used in improvisatory workshops, every creative decision and every conversation regarding Storyteller is sparked and led by the notation’s constraint.

amy bryce a kinder society 2021

The score for immersive opera A Kinder Society is another example where Bryce consciously navigates notational constraint and flexibility.11 Bryce wanted the singers to be free to respond to the unfolding situation as it happened, which could only occur if their character’s personality was made clear in the score. Bryce defines these roles so that the vocalists can embody their characters enough to be able to respond as them. Through this constraint, the singers are given freedom to make the piece come to life, forced to make decisions by the score’s non-linearity, for example. Therefore, freedom is enabled by the constraint that Bryce set out in notation:

[With A Kinder Society,] I was looking very specifically at how to create things that were non-linear: how to give singers enough to be able to embody a character, and respond to audience members, and still be musical and still feel to be within an operatic scene that is […] musically happening in time, but in a non-linear […] responsive sense. […] Quite crucially, all of these scores involve a certain level of actual physical interactivity from the performer. You don’t just read it from one direction to the other; [you] actually have to really float through.

With these aims, Bryce decided to create a different notated score for every scene, each holding an abundance of musical prompts — too many to be achieved in any singular performance, leaving the direction of each performance up to the instrumentalists. Bryce states: ‘it’s important that through score, you do not feel like you’ve ever reached the bottom of the possibility of that world. And that’s what the [notational] complexity is for: so that if you need to go finding things, you can just go on a hunt; you go searching and the score will keep giving and giving’. Notated elements are all precisely described, or constrained, but the instrumentalist has to decide whether to act on them. By its constraint, the score is part of the musical process, working alongside the composer and any score-interpreter. Such constraint links composer to interpreter, because the composer limits or enables musical decisions on behalf of the instrumentalist. The notation, which mediates constraint, is seen to have an active and integral role in the musical process by its affordance of decision-making.

The complexity of Bryce’s scores offers more constraint than Bröndum’s, yet it is Short Circuit whose outcome has become predictable. Where both composers aimed for the interpreters’ creative ‘freedom’, Bryce’s very complex notation is arguably more successful than Bröndum’s sparse notation. Therefore, it can be seen that well-considered use of notational constraint affords greater creative freedom in interpretation.

notational constraint is not always complex

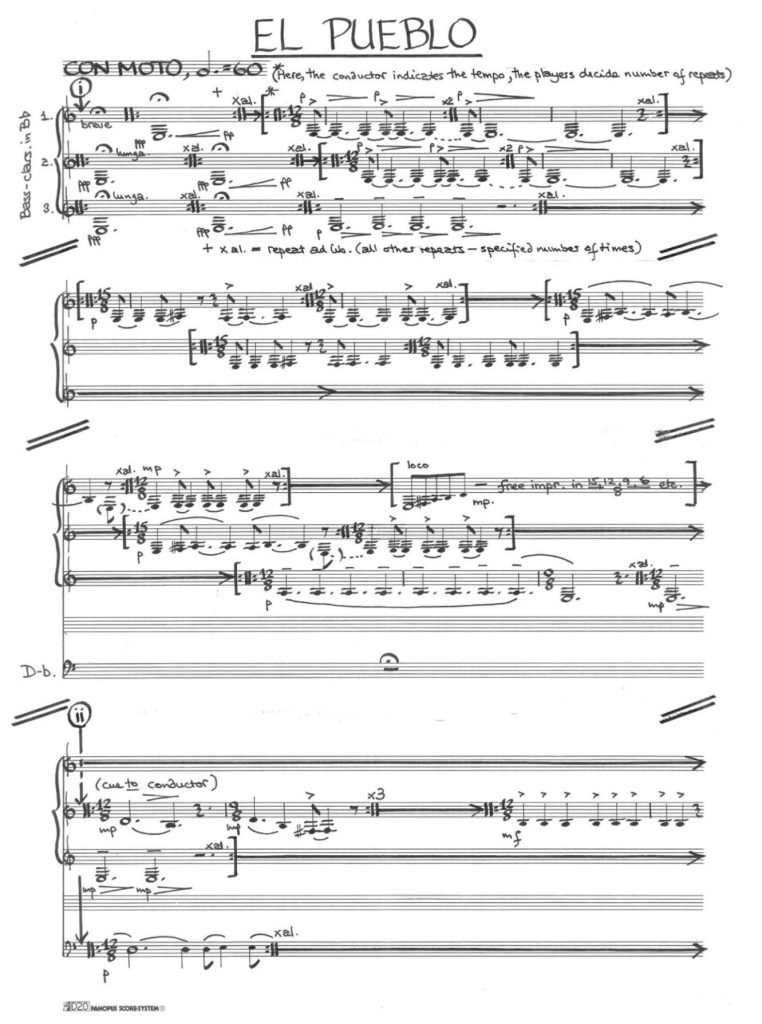

It should be noted that Bryce’s complex scores provide just one example of successful notational constraint: is not the case that interpretational freedom requires notational complexity, because complexity is not equivalent to constraint. For example, William Sweeney uses non-linearity in El Pueblo (1989) to similar effect: this is not notated with particular complexity, but still meets his aim to achieve a different musical result with each realisation. In the opening, the score (and conductor) determines the tempo, while the instrumentalists decide on the number of times to repeat their musical ‘cell’ (see Fig. 3). This clear notation, using simple text and conventional ‘repeat’ markings, gives each instrumentalist creative freedom in deciding how the piece takes shape, while working within a fixed tempo and with specific musical cells chosen by Sweeney. His careful consideration of the balance between openness and constraint leads to interpretational freedom: Sweeney guides the musicians through the structure; a sound-world that the instrumentalists would not otherwise be part of. Indeed, Bryce speaks of composing as ‘world-building’. Sweeney invites the instrumentalists to make his world their own, bringing them ‘in[to] the mix’ with freedom by constraint: ‘you can see the, you know, the thing of “in tempo”, but it’s free’.

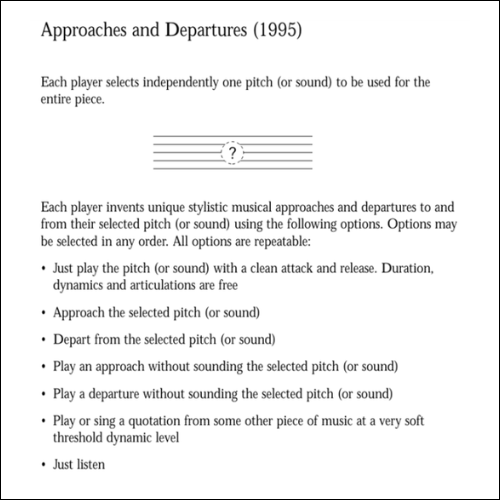

Simple text scores can also successfully guide musical practices with notational clarity. See Pauline Oliveros’ Approaches and Departures (Fig. 4). This score allows the interpreter to experience a new method of Deep Listening, affording freedom by prompting the interpreter’s continual engagement with decision-making. Benjamin explains:

Pauline Oliveros’ pieces […are] not just all listening pieces. Like, The Tuning Meditation has very different and specific way of being within it than you know, Approaches and Departures or something. And so I think that without, you know… If you got rid of those scores and you just said, “let’s all do some deep listening”, it would kind of all amalgamate into one thing. And I think the specificity of those moments of interaction between musicians is really special in Pauline’s music.

Similarly to Short Circuit, the score for Approaches and Departures dictates a number and the interpreter subsequently chooses that number of pitches: ‘Each player selects independently one pitch (or sound) to be used for the entire piece’. Here, the word ‘independently’ works to negate performances becoming similar: the interpreter is to choose their pitch (or sound) before the performance has begun, independently of the other performers’ choices. In this respect, the number of pitches (or sounds) is limited to one; but the choice of pitches (or sounds) is endless. An interpreter, being forced to choose only one from an infinite number of pitches (or sounds), has to: firstly, acknowledge the pitches (or sounds) available to them; secondly, assess their pitch (or sound) preference;12 and, finally, exercise their freedom by performing their own sonic preference. These decisions are made freely within the constraint set out in notation; and might not have otherwise been made. The text is clear, precise, and considered, unambiguously communicating (as much as possible) what is constrained, and what is ‘free’.

in conclusion (for now)

So, it can be understood that, in order for notation to be ‘consistently useful’ (to use Mira Benjamin’s words), it must afford creativity by constraint. My next post will build on this one, discussing Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory and Clarke & Doffman’s concept of ‘distributed creativity’ to contribute to an understanding that notation is a collaborative agent in musical processes by the constraint it affords.

footnotes

- This is supported by Cook’s argument that notation is most accurately understood as describing what an instrumentalist should not do (21). ↩︎

- ‘Affordance’ is a term coined by James J. Gibson (for example, see: “The Theory of Affordances”). It refers to what an environment offers an animal (119), not in terms of abstract physical properties (for example, a chair is flat; large; heavy) but in relation ‘to the posture and behaviour of the animal being considered’ (the chair is a suitable size, height, and structure for a specific human) (120). ↩︎

- For example, see Latour’s 2005 book, Reassembling the Social. ↩︎

- Previous knowledge forms a set of preferences and priorities regarding: how music might sound; how an instrument might be played; how notations might be interpreted; and so forth. ↩︎

- These decisions might regard: pitch, dynamic, pulse, tempo, etc. ↩︎

- Dingle states: ‘So many of the performances that you hear of graphic scores, or other things using musical graphics, tend to conform to a predictable aesthetic. […] The same goes for much free improvisation. […] It is not truly free improvisation, or liberation from the tyranny of Western stave notation in the case of musical graphics, but a style improvisation of a predictable aesthetic’ (138); ‘There’s also the danger with […] aleatoric notation that you get the “wobbly bridge” problem, which is that people may start walking separately but quite rapidly get pushed into step with each other’ (325). ↩︎

- Unfortunately, the question regarding how much constraint is ‘sufficient’ is too vast for this dissertation to adequately discuss. For more information, consult: Eva Teubal et al., Notational Knowledge; Rolf Inge God, “Ecological Constraints”; and Sophia R. Cohen, “The Development of Constraints”. ↩︎

- Benjamin said: ‘If the score is consistently useful, then it’s a good score in my book.’ ↩︎

- Similarly, with Bröndum’s piece Fluttering: ‘In the contrabass clarinet solo […] the square disjunct symbols are often interpreted by the musician as multi-phonics, even though it is not explicitly noted in the score’ (649). ↩︎

- Bryce’s introduction to the score can be found on YouTube (“Storyteller – Introductory Thoughts of Sorts”); and a PDF ‘instruction manual’ can be consulted via www.amybryce.co.uk/storyteller (Accessed 13 Jun 2024). ↩︎

- A Kinder Society is available to watch in full on YouTube (“A Kinder Society – Amy Bryce.”). ↩︎

- This is most likely based on differences perceived between pitches (or sounds), but could also be driven by chance operations, for example. ↩︎

list of references

“A Kinder Society – Amy Bryce.” YouTube, uploaded by Amy Bryce, 10 Sep 2021, https://youtu.be/90Iz1vNa84I?si=8UUeIKuOIJxz7zJs. Accessed 14 Jun 2024.

Anderson, Julian and Christopher Dingle. Julian Anderson: Dialogues of Listening, Composing and Culture. The Boydell Press, 2020.

Barrett, Richard. “Notation as Liberation.” Tempo, vol. 68, no. 268, 2014, pp. 61-72. doi.org/10.1017/S004029821300168X. Accessed 13 May 2024.

Bayley, Amanda and Neil Heyde. “Communicating through Notation: Michael Finnissy’s Second String Quartet from Composition to Performance.” Music Performance Research, vol. 8, 2017, pp. 80-97. proquest.com/scholarly-journals/communicating-through-notation-michael-finnissys/docview/2424658020/se-2. Accessed 4 Apr 2024.

Benjamin, Mira. Personal Interview. 8 May 2024.

Bryce, Amy. Personal Interview. 17 Apr 2024.

Cardew, Cornelius. “Notation—Interpretation, Etc.” Tempo, vol. (unknown), no. 58, 1961, pp. 21–33. doi.org/10.1017/S0040298200045873. Accessed 4 Apr 2024.

Clarke, Eric F. and Mark Doffman, editors. Distributed Creativity: Collaboration and Improvisation in Contemporary Music. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Cohen, Sophia R. “The Development of Constraints on Symbol-Meaning Structure in Notation: Evidence from Production, Interpretation, and Forced-Choice Judgements.” Child Development, vol. 56, no. 1, Feb 1985, pp. 177-95. doi-org/10.2307/1130184. Accessed 13 Jun 2024.

Gibson, James J. “The Theory of Affordances”. In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 1st ed., edited by James J. Gibson, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015, pp. 119-36.

God, Rolf Inge. “Ecological Constraints of Timescales, Production, and Perception in Temporal Experiences of Music.” Empirical Musicology Review, vol. 9, no. 3-4, 2014, pp. 224-29. doi.org/10.18061/emr.v9i3-4.4442. Accessed 13 Jun 2024.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press, 2005.

McKay, Tristan. A Semiotic Approach to Open Notations: Ambiguity as Opportunity. Cambridge University Press, 2021. doi.org/10.1017/9781108884389. Accessed 4 Apr 2024.

“Storyteller – Introductory Thoughts of Sorts.” YouTube, uploaded by Amy Bryce, 3 Jan 2022, youtu.be/hZW433j8EVE?si=Ocq19aAlUb-Hl3Em. Accessed 13 Jun 2024.

Sweeney, William. Personal Interview. 21 Mar 2024.

Teubal, Eva et al. Notational Knowledge: Historical and Developmental Perspectives. Sense Publishers, 2007.

Leave a Reply