can sound be described?

Following ideas introduced in notation is graphic, this post discusses another common notational categorisation: prescriptive vs. descriptive notation.

The idea that prescriptive and descriptive notations are exclusive categories is frequently adhered to in music scholarship (for example, see Kanno). In such sources, the term ‘prescriptive’ refers to notation as a symbol that tells the player to respond with a physical action (which will in turn produce sound).1 Presented in opposition, ‘descriptive’ notation is defined as a set of symbols that describes the sound to be made (presumably leaving the decision of action to the performer, so long as it achieves the sound described).

However, this argument stumbles on its implication that sound can be accurately described in notation (for example, see Kanno 232 and Lepper et al. 1):2 there are some elements of sound that are unable to be notated, for example precise timbre or ‘grain’ (Barthes; see also Francois).

The assumed aim that notation is a method to record exactly how music sounds indicates how deeply the traditional work concept is embedded in the discourse surrounding music notation. Indeed, ‘prescriptive’ notation is often referred to in relation to early and new music;3 whereas ‘descriptive’ notation most frequently pertains to staff-notated music c.1800 onwards.4

an inclusive reading

Understanding that musical practice is embodied, I propose that all notation is both prescriptive and descriptive: it can be seen that whenever notation describes an attribute of a sound to be played, to some extent it also describes how that sound will be played. The interpreter reads the ‘description’, and consciously or subconsciously translates this into a method of sound production (a ‘prescription’).

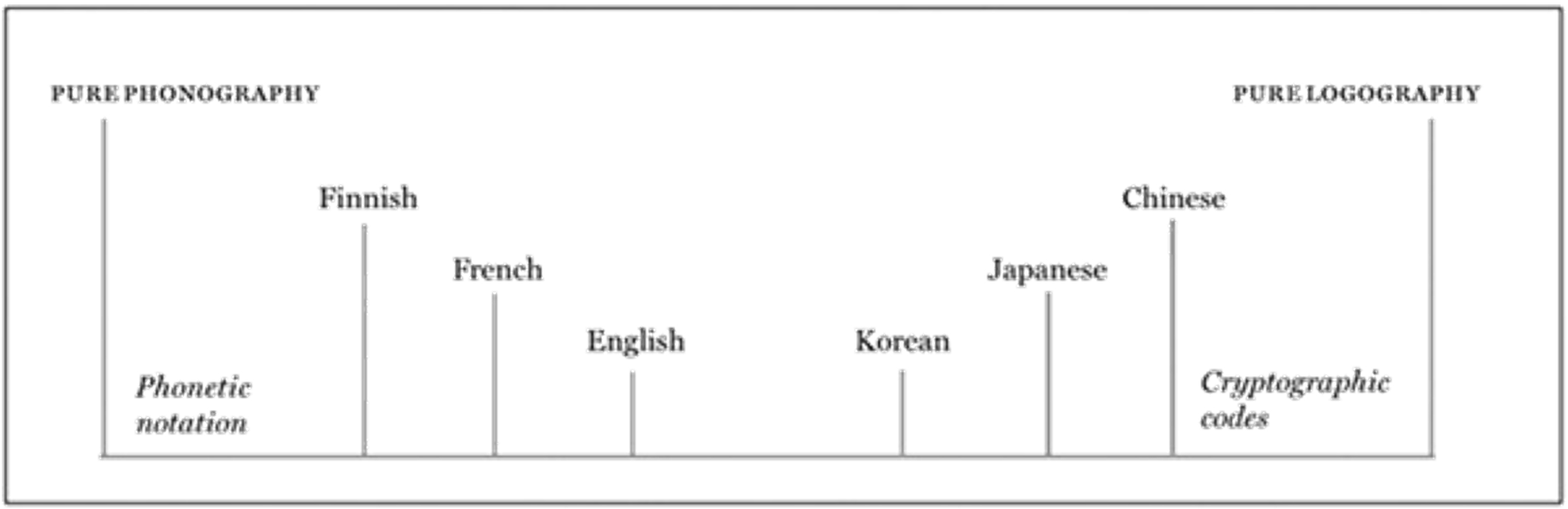

This makes such categorisation of notational systems far more complex than a simple dichotomy. Andrew Robinson presents a linguistic parallel in The Oxford Companion to the Book, where he states that all writing systems are necessarily a combination of phonographic and logographic elements. (Phonography is literally defined as ‘sound writing’ and is analogous with notating ‘descriptively’; logography, or ‘symbol writing’, relates to notating ‘prescriptively’.)5 Robinson explains:

What differs between writing systems—apart from the forms of the signs, of course—is the proportion of phonetic to semantic signs. The higher the proportion of phonetic representation in a script, the easier it is to guess the pronunciation of a word. There is thus no such thing as a “pure” writing system, that is, a “full” writing system capable of expressing meaning entirely through alphabetic letters or syllabic signs or logograms— because all “full” writing systems are a mixture of phonetic and semantic signs. How best to classify writing systems is therefore a controversial matter. Nevertheless, classifying labels are useful to remind us of the predominant nature of different systems.

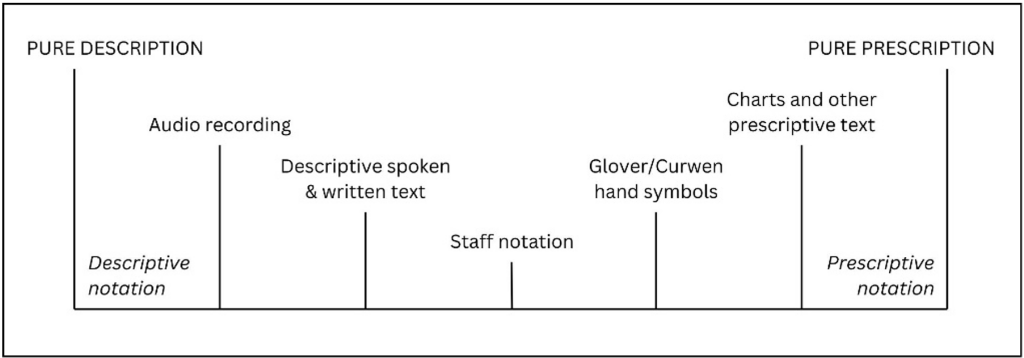

Similarly in music notation, the terms ‘prescriptive’ and ‘descriptive’ can be used to highlight the preponderance of a type of signification within a system that can never be ‘purely’ prescriptive or descriptive.

case study

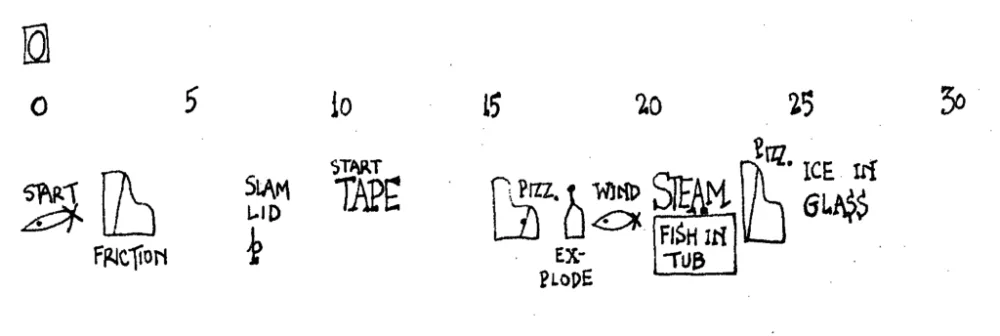

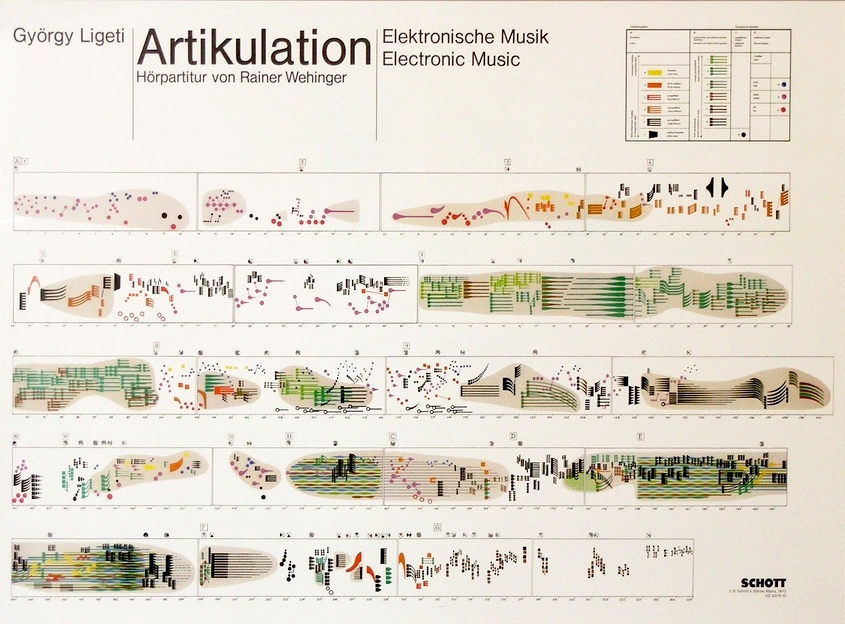

The usefulness of this method of categorisation is showcased in analysis of Ligeti’s Artikulation (1958), for example, for which two notated scores exist. Firstly, Ligeti’s ‘prescriptive’ charts, tables, and algorithms informed his own practice (Ligeti’s subsequent recording is commonly understood to comprise the piece);6 and secondly, graphic designer Rainer Wehinger created a more ‘descriptive’ listening score (“Hörpartitur”), which was commissioned by Ligeti and created in response to Ligeti’s recording (see below). The respective notations are representative of the scores’ unique functions: thus, notational categorisation can make clear the functional differences that separate the scores.

This categorisation might also avoid unfair judgement of a notation system by aims it never sought to uphold. For example, Taruskin scathingly remarks that Wehinger’s listening score: ‘served no […] practical purpose—not even for analysis, since the sounds were not represented with enough specificity as to their exact frequency or duration […] they were rendered impressionistically, by fancifully executed shapes of arbitrary design’. This evaluation is found on an understanding that the score aims to be prescriptive where, in actuality, Wehinger’s score is largely descriptive: although prescribing a certain way of listening, the shapes, colours, and symbols seek to describe different sounds, textures, and techniques to guide the listening practice.

a spectrum

Robinson presents this diagram (above) to exemplify the spectrum, rather than dichotomy, between pure phonography and pure logography. Music notation systems can be similarly depicted (for example, see below), which exemplifies the parallel between these models and highlights this system’s relevance to musicology. With respect to Ligeti’s Artikulation then, Ligeti’s initial score sits towards the right-hand of the chart, largely prescribing the electronic actions that need to take place for the sounds to occur; Wehinger’s listening score is to the left, mostly describing sound but also prescribing a listening practice.

in conclusion

By understanding that all notation sits on a spectrum between ‘prescriptive’ and ‘descriptive’ — and is never solely one or the other — I define that: notation signifies a musical idea, which is realised through action, led by listening and perhaps an expectation of the sound that might arise. This concise definition describes what I think music notation is, but opens up the question (that my next post will discuss in more detail): how is music notation translated into sound?

footnotes

- Prescriptive notation is often seen to invite the performer into the creative process because, as Kanno explains, it treats notation as mediation rather than representation (231). ↩︎

- The contributing authors of the article, “Diminuendo Al Bottom”, are Markus Lepper, Michael Oehler, Hartmuth Kinzler, and Baltasar Trancón y Widemann. ↩︎

- Here, early music is defined as written prior to the prevalence of the traditional work-concept (which begun c.1800, according to Goehr). New music is understood to begin with those composers pushing against the traditional work-concept in post-World War II experimentalism (John Cage, for example) and avant-garde (Pierre Boulez, for example). ↩︎

- See the argument that the traditional work-concept formed c.1800 in Goehr, The Imaginary Museum. ↩︎

- Logography refers to symbols that represent entire words without relating to their pronunciation. ‘Prescriptive notation’ similarly depicts an entire musical idea rather than its constituent sound descriptors. ↩︎

- It should be noted that Richard Taruskin argues that: Ligeti’s Artikulation had ‘no score (and no possibility, therefore, for analysis of the result), for the composer had worked by ear on the basis of rough charts. There was no need for a prescriptive notation since electronic music, once fixed on tape, required no performers at all, just playback equipment’. This treats the ‘Score as Work’, implying that prescriptive notation is only useful for interpreters trying to sound the Work. This dissertation challenges the usefulness of the traditional work-concept, arguing that Ligeti’s charts are a form of notated score. ↩︎

list of references

Barthes, Roland. The Grain of the Voice: interviews 1962-1980. Translated by Linda Coverdale, Cape Publishing, 1985.

Francois, Jean-Charles. “Writing without representation, and unreadable notation”. Perspectives of New Music, vol. 30, no. 1, Winter 1992, pp. 6-20. doi.org/10.2307/833281. Accessed 14 May 2024.

Goehr, Lydia. The Imaginary Museum of Music Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music. Rev. ed., Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kanno, Mieko. “Prescriptive Notation: Limits and Challenges.” Contemporary Music Review, vol. 26, no. 2, 2007, pp. 231-54. doi.org/10.1080/07494460701250890. Accessed 14 May 2024.

Lepper, Markus, et al. “Diminuendo Al Bottom—Clarifying the Semantics of Music Notation by Re-modeling.” Public Library of Science One, vol. 14, no. 11, 2019. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224688. Accessed 14 May 2024.

Robinson, Andrew. “Writing Systems.” In The Oxford Companion to the Book, Oxford University Press, 2010. www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198606536.001.0001/acref-9780198606536-e-0001. Accessed 9 Jun 2024.

Taruskin, Richard. “Chapter 1: Starting from Scratch.” In The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Late Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 1-54. www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume5/actrade-9780195384857-div1-001014.xml. Accessed 9 Jun 2024.

Leave a Reply