Scholarship regarding contemporary music notation often negatively refers to the process that occurs between musical notation and its sonic realisation as an inexplicable ‘gap’. Mieko Kanno believes that this gap highlights the ‘inadequacy of notation’ (234) in being unable to describe sound accurately. However, I believe that the gap is notation’s greatest strength, because it is where creativity is realised.

the creative gap vs. the Werktreue

The gap is only an inadequacy where scholars still confine themselves to the traditional work-concept, which holds that the Werktreue is impossible to accurately grasp: in that situation, any notation will fall short.1 In 1983, Robert Black evidenced such constraint to Werktreue by stating that any performance of a notated score will inevitably harm ‘the composer’s original aims’ because of notation’s inability to portray sound precisely (128). It is surprising that Kanno in 2007 was still holding the same view following the rebuttal to that work-concept that begun in the 1990s (for example, see scholarship by Goehr;2 Small;3and Leech-Wilkinson)4. Kanno is not alone: in fact, wherever contemporary music notation is discussed in scholarship, it is described in similar terms. See Jeanne Bamberger in 2005 who, stating that music notation in contemporary music ‘provides unambiguous conduit from composer to performer’, still believes that something is ‘lost’ in notation’s translation process (144). Bamberger assumes that notation aims to be unambiguous, which contradicts my findings (referring to Eco, for example). As such, she misunderstands the gap as a negative space where ideas are lost, not gained.

Even more recently, Roger Heaton in 2012 asks: ‘Is there an interpretive gap in [contemporary music] between fidelity to the text and the composer’s intentions?’ (100). In relation to contemporary performance practice, he asks whether notation ‘provide[s] sufficient information for a satisfactory rendition’; and whether notation leads to ‘appropriate expression’. This holds the view that the composer is the Creator of the Work, where the Work is the notated text; and the performer is a puppet, whose only job is to sound the Work into being (also see Black 121). I agree with Goehr, Small, and Leech-Wilkinson (for example), that the traditional work-concept does not accurately describe musical processes. Instead, I work alongside the theories of Clarke & Doffman and Cook (for example), witnessing music as a distributed creative process.

notational openness

It can be argued that this gap between notational intent and notation outcome is a result of notation’s openness. An artwork’s ‘openness’ relates to its interpretational ambiguity, which is governed by the artistic conventions of contemporary culture (Eco). Eco states that art is more ambiguous the less it defers to traditional conventions; that such conventions limit ambiguity by narrowing the field of ‘acceptable’ interpretation. Eco argues that interpretation can be vast, varied, and indeed ambiguous in the modern open work, because traditional regulations do not apply. David Robey summarises: ‘traditional art confirms conventional views of the word, whereas the modern open work implicitly denies them’ (in Eco xi). As Andrea Valle argues in Contemporary Music Notation, notation (‘sign production’) happens after the fact and so is already a ‘non-identity’ (5); notation is always ‘synthetic’ (6-7). Along these lines, every notation brings about numerous interpretative possibilities (8) because notation is concise by definition (6). Literature widely agrees that all notation is essentially partial, incomplete, and selective (for example, see Bamberger 134-4).

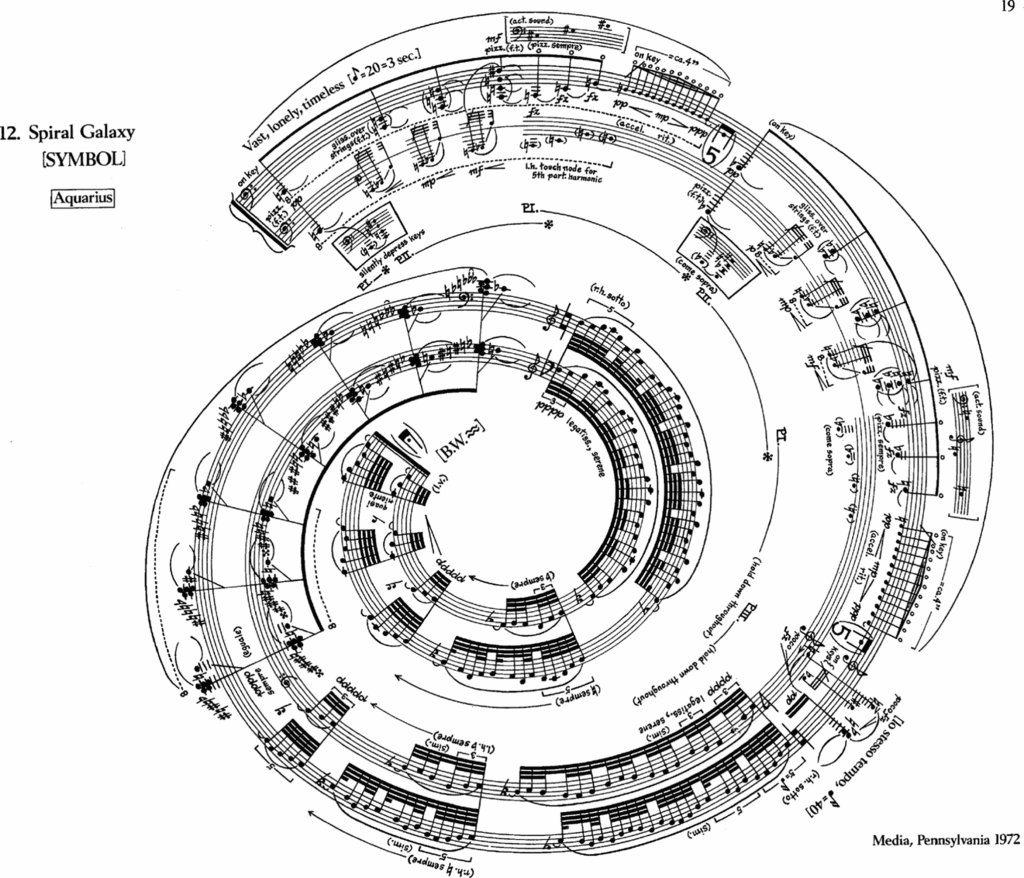

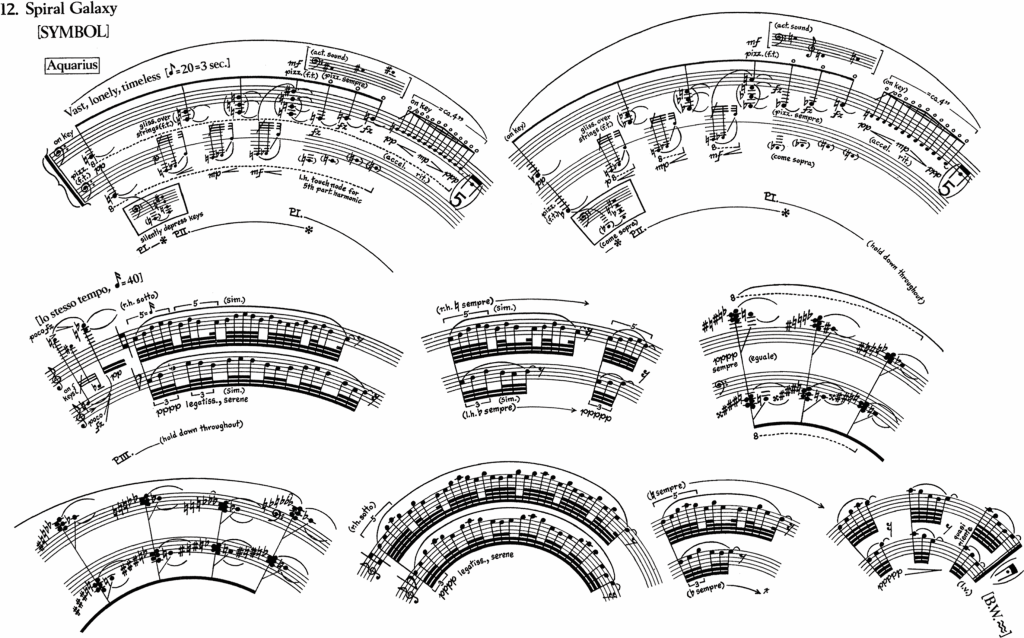

Therefore, the translational process required for an interpreter to realise notation into sound (heard or imagined) is due to notation’s openness; the intrinsic visuality of contemporary music notation that actively influences perception and interpretation. In this respect, Christopher Dingle states: ‘[The] psychological impact of the notation for the performer is critical to how a piece sounds’ (Anderson and Dingle 118). Similarly, McKay discusses the circular score for George Crumb’s Spiral Galaxy (1979) (3-4) (See Fig. 1), explaining that many pianists make themselves an easily-readable performance score by cutting up and arranging the staves in a linear fashion (see Fig. 2).

where (what) is ‘the music’?

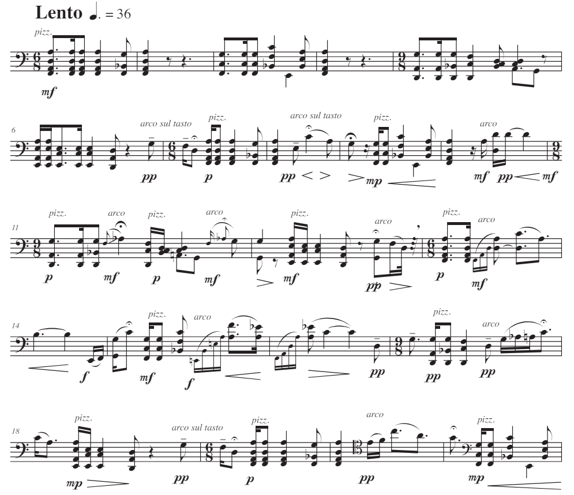

McKay ponders whether part of the ‘music’ gets lost by this process: ‘even though the pitch, rhythm, and dynamic content of the original and reconstructed scores remain the same, […] the reconstruction itself changes something fundamental about what the [score] communicates to the performer’ (3-4). Similarly, Sweeney speaks of a part of music that cannot be written explicitly in the score: the feel, which is signified in the notational presentation of the score, but not by any single symbol. He describes Mar Rós a Chaill, where ‘the melody is in snatches. [… It’s] that thing of […] everything’s in time but just some things are removed from time. [… It can be difficult] trying to keep the overall rhythm of the piece. Use the pauses, but keep in the back of your mind that it goes back into this [timing]’ (xlii) (see Fig. 3).

Mar Rós a Chaill is an arrangement for solo string instrument of the final piece in Sweeney’s opera An Turus (The Journey). Pizzicato chords use dotted rhythms to build a pulse; and the melody takes shape in poignant, lyrical, arco interjections floating outside musical time. The immediate psychological effect of this notated score exemplifies Sweeney’s description. Ignoring any knowledge of staff notation, the melody that is ‘removed from time’ looks isolated and vulnerable amongst the blacker, repeated visual motif providing the background pulse. Tenuto and slur markings work alongside hairpin crescendos and diminuendos to differentiate the appearance of the melody from that of the chords. Thus, Sweeney’s musical intention becomes clear by simply observing the notated score, without needing to understand what each individual symbol signifies. Crumb’s spiral score works similarly. It can therefore be argued that contemporary notation’s openness sparks creative interpretation without dictating: notation’s openness gives space for an underlying musical ‘feel’ to be represented and interpreted indirectly.

in conclusion (for now)

I believe ‘music’ is neither notated score nor performance alone, but something that occurs continuously throughout any musical process. In this respect, the creation of music is always a distributed process, because any musical outcome is the result of numerous affordances.

As such, notation is particularly interesting to me because it physically documents at least one stage in the evolving creation of a work of music. The ‘gaps’ in musical processes — the spaces where an act of translation must occur to transform a musical idea into musical sound — fascinate me because they are so often overlooked; in my opinion these gaps are where the ‘music’ is.

Future posts plan to discuss ideas of openness in more detail, looking into ideas of constraint and freedom in notation processes, as well as discussing definitions of ‘music’ more broadly.

footnotes

- Scholarship evidences a similar discourse in linguistic semiotics. Ferdinand de Saussure argues that a ‘signifier’ is fixed to its ‘signified’ (235); whereas Umberto Eco states that ‘meaning’ is dependent on context where ‘information’ is not (52-3). In musicology then, Eco believes that one notation affords multiple readings based on context; where Saussure assumes the ‘score as Work’. ↩︎

- See, for example, Lydia Goehr: The Imaginary Museum. ↩︎

- See, for example, Christopher Small: Musicking the Meanings of Performing and Listening. ↩︎

- See, for example, Daniel Leech-Wilkinson: “Compositions, Scores, Performances, Meanings”. ↩︎

list of references

Anderson, Julian and Christopher Dingle. Julian Anderson: Dialogues of Listening, Composing and Culture. The Boydell Press, 2020.

Bamberger, Jeanne. “How the conventions of music notation shape musical perception and performance.” In Musical Communication, edited by Dorothy Miell et al., Oxford University Press, 2005, pp.143-70. doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198529361.001.0001. Accessed 16 Apr 2024.

Black, Robert. “Contemporary Notation and Performance Practice: Three Difficulties.” Perspectives of New Music, vol. 22, no. 1/2, 1983, pp. 117–46. doi.org/10.2307/832938. Accessed 14 May 2024.

Clarke, Eric F. and Mark Doffman, editors. Distributed Creativity: Collaboration and Improvisation in Contemporary Music. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Cook, Nicholas. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Eco, Umberto. The Open Work. Translated by Anna Cancogni, Harvard University Press, 1989.

Goehr, Lydia. The Imaginary Museum of Music Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music. Rev. ed., Oxford University Press, 2007.

Heaton, Roger. “Contemporary Performance Practice and Tradition.” Music Performance Research, vol. 5, no. (unknown), 2012, pp. 96-104. proquest.com/scholarly-journals/contemporary-performance-practice-tradition/docview/2082950437/se-2. Accessed 4 Apr 2024.

Kanno, Mieko. “Prescriptive Notation: Limits and Challenges.” Contemporary Music Review, vol. 26, no. 2, 2007, pp. 231-54. doi.org/10.1080/07494460701250890. Accessed 14 May 2024.

Leech-Wilkinson, Daniel. “Compositions, Scores, Performances, Meanings”. Music Theory Online, vol. 18, no. 1, Apr 2012. proquest.com/scholarly-journals/compositions-scores-performances-meanings/docview/1619653358/se-2. Accessed 3 Jun 2024.

McKay, Tristan. A Semiotic Approach to Open Notations: Ambiguity as Opportunity. Cambridge University Press, 2021. doi.org/10.1017/9781108884389. Accessed 4 Apr 2024.

de Saussure, Ferdinand. Writings in General Linguistics. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Small, Christopher. Musicking the Meanings of Performing and Listening. New England University Press, 1998.

Sweeney, William. Personal Interview. 21 Mar 2024.

Valle, Andrea. Contemporary Music Notation: Semiotic and Aesthetic Aspects. Translated by Angela Maria Arnone, Logos Verlag Berlin, 2018.

Leave a Reply